I mainly write fantasy. Everything is fantasy, of course. All fiction, I mean. We tell stories to make sense of our lives, of people, of the world, so we simplify, condense and, perhaps above all we impose a narrative structure and a terminal point. Fiction is to our lives what gardening is to nature. And we do not respect the boundaries between ostensible fiction and ostensible reality. John Fowles once accused his readers of hypocrisy, does not the reader fictionalise their own past, gild it, blacken it, censor it, tinker with it? Is memory our novelisation of the lives we have led?

Yet, that is not quite what I wish to address. What I wish to argue is that all novels, or, at least, the better ones, take you to another place, to a universe that the author creates for their stories. Each author builds a world that has its own voice, feel, taste or tang, and also its own rules, and conventions, its own logic. All of these things ensure that the author’s world is not ours. This is as true of a contemporary setting as of an evocation of some other time or place. Take a couple of obvious examples to illustrate the point. Do we suppose that the London of Dickens’s contemporaries felt to them like the London of his novels, with all the exaggeration, the grotesqueries? If it had, we would hardly need the word ‘Dickensian’ to describe his written world. Do we believe that, even within that top percentile of inter-war idle rich, the real world ever resembled a PG Wodehouse novel? These are not subtle examples, but you can find this true of any book worth reading. I haven’t read a lot of crime fiction, but I once picked up one of Sir Ian Rankin’s books and, immediately, I knew that the Edinburgh of Inspector Rebus was a distinctive version of that City. It had an atmosphere all its own.

Another thing that I believe a good book should do is to leave the reader, at its conclusion, changed. There will be a thought or insight, a mood or emotion, a haunting, a legacy after the book is finished.

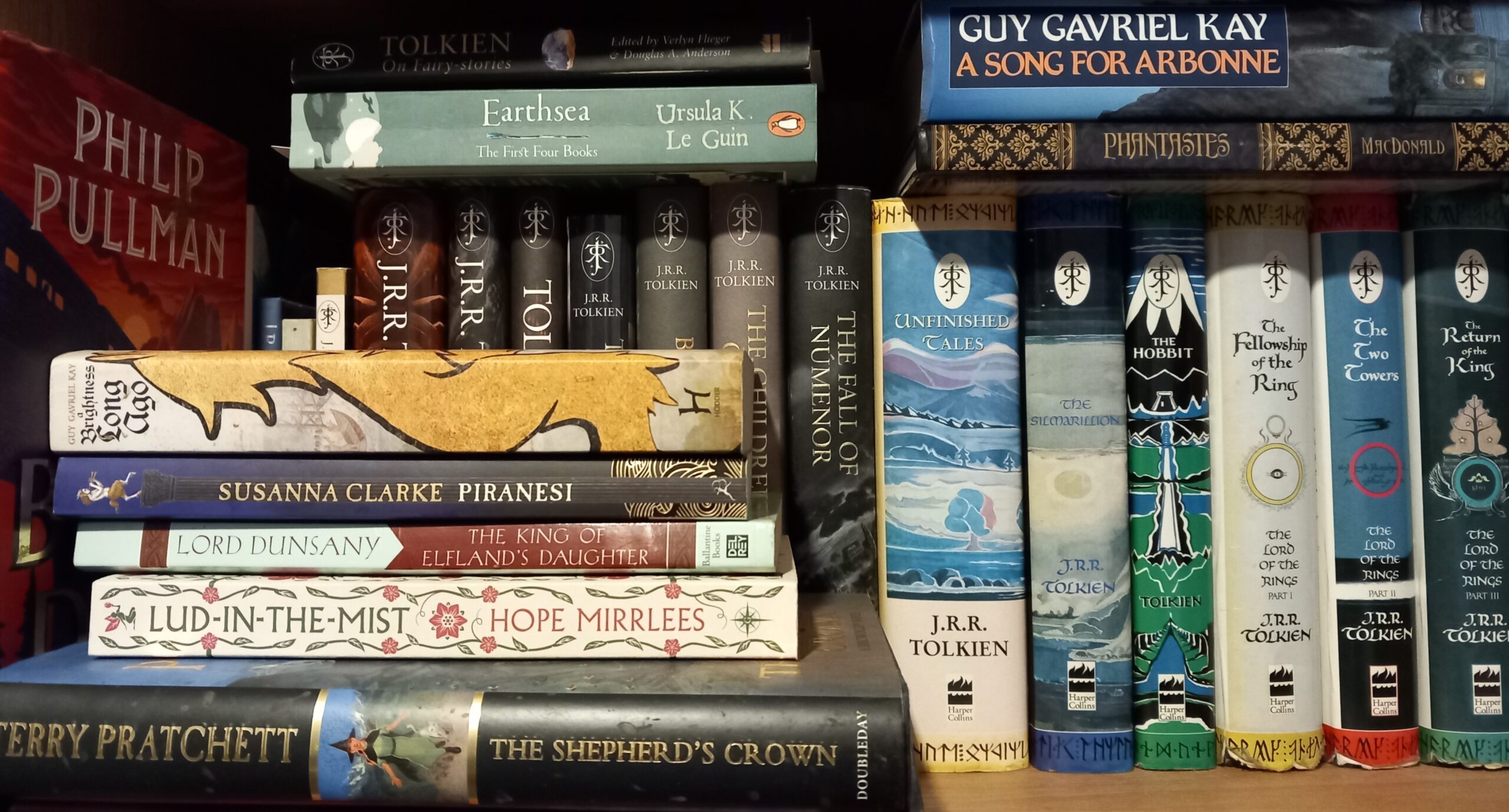

Yet this is starting to sound very much like JRR Tolkien’s perilous realm, or Ursula K Le Guin’s Elfland. For them, to qualify as fantasy literature, a book must take you to a different place and that journey must change you. Don’t all good books do that?

What, then, makes a book ‘fantasy’? I suppose one could say it is the inclusion of fantastical elements, however defined. One could say that fantasy is a genre where one is presented with a world that is not this one. That is certainly true of High Fantasy. Some fantasy, however, ostensibly takes place in our world. Some fiction makes our own world fantastical. Where do we place Gaiman’s Neverwhere, RL Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde, Chesterton’s The Man Who was Thursday, or García Márquez’s magical realism? When, in practical terms, does what is ostensibly a representation of our world become fantasy? If, for example, we stray into a near future dystopia? Anything in the future is, by definition, speculative. What about historical novels? The further back a setting goes, the less likely it is to represent that past with anything like realism. Can a novel featuring Neanderthals be anything more than fantasy?

This is not to say that there is no such thing as fantasy. There is, it’s a recognisable genre. Nowadays much of it is unoriginal – moving the furniture in Tolkien’s attic, as I believe the late great Sir Terry Pratchett put it – and much of it is written in the sort of immersion-breaking demotic language Le Guin warned against in the early 1970s, and some of it is simply atrocious. Yet much of it is beautiful, inspiring and even profound. The novel is one of the most flexible art forms; one can do limitless things with it, put anything the human imagination can conceive into one. Fantasy is a form that allows the beauty of imagination to unfold without the limitation of what has been or could be found in our world and that is a resource that can be used to explore anything from love, death and sacrifice to Jungian self-actualisation and, indeed, satire.

So, avoiding tropey, indifferently written fantasy that has little more to offer than shallow adventurism or a hackneyed teen romance is one thing. Condemning the genre out of hand, is another thing, because, if you read any fiction at all, you are inevitably to some extent already reading fantasy. If you eschew fiction altogether – a rather Nineteenth Century male view – then, I am afraid, you are merely opening yourself to Fowles’s charge of hypocrisy. Your memory and beliefs about yourself have made you a fantasist already.

EPS James